November 22, 1963—a date burned into the memories of all Americans of a certain age, much like September 11, 2001, is in the memories of younger generations. Even today, some fifty-six years later, anyone alive at that time can tell you exactly where they were, what they were doing, and what they were thinking when the news headlines flashed around the world that President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was assassinated on the streets of Dallas, Texas.

As we mark the 56th anniversary of the assassination, many questions about Kennedy’s murder, and murderer, remain unanswered. Just who was Lee Harvey Oswald, the alleged assassin of JFK? What did our government know about Oswald, his unstable history, his strange travels around the world, his even stranger relationships with political radicals of all stripes, and when did they know it? Perhaps most intriguingly, did Oswald have accomplices and was he the point man of a larger conspiracy?

The American people seem to think so. A recent Gallop poll showed that 61 percent of the public believes individuals other than Oswald were involved, or played some role, in the President’s murder. This apparently included Secretary of State John Kerry who in 2013 told NBC’s Tom Brokaw in an interview, “To this day, I have serious doubts that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone”—an extraordinary admission from a leading government official. When asked to elaborate, Kerry said, “I certainly have doubts that he was motivated by himself, I mean I'm not sure if anybody else is involved—I won't go down that road with respect to the Grassy Knoll theory and all that—but I have serious questions about whether they got to the bottom of Lee Harvey Oswald's time and influence from Cuba and Russia.”

Additionally, Robert Kennedy Jr. (son of JFK’s brother, Robert Kennedy) recently said that his father privately believed there was a lot more to the story than what the government officially claimed. Speaking to Charlie Rose in front of a large audience in Dallas in November, 2013, Kennedy revealed that his father, Robert Kennedy, believed the Warren Report—which concluded Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone in the assassination—was a “shoddy piece of craftsmanship.” Rose asked Kennedy if he believed his father may have felt "some sense of guilt because he thought there might have been a link between his very aggressive efforts against organized crime [and the President’s assassination]." "I think that's true,” Kennedy replied. “He talked about that. He publicly supported the Warren Commission report but privately he was dismissive of it." He told Rose, and a stunned audience, that his father was "fairly convinced" that others were involved in his brother’s murder.

Conspiracy or not, though, the only way to explain what transpired in Dallas that fateful November day requires that we explain the man at the heart of the story, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Those who have studied Oswald’s life, including no less than five Congressional committees, as well as countless researchers, writers, and journalists over the years, can only conclude that he was a person of incredible strangeness, contradictions, and whose life was (and still is to some extent) cloaked in a fog of intrigue and secrecy. G. Robert Blakey, who in 1976 led the second major governmental investigation of the Kennedy assassination, put it best: “Lee Harvey Oswald is a mystery wrapped up in an enigma, hidden behind a riddle.”

However, to the extent that the life of Lee Harvey Oswald still remains a mystery, this much is certain: American intelligence knew a great deal more about Kennedy’s assassin before November 22, 1963, than they have ever admitted to publicly—an inconvenient truth that, in the assassination’s aftermath, compelled them, for political and national-security reasons, to go to great lengths to cover up their true knowledge of the man who killed Kennedy.

From Russia With Love

Oswald and his wife Marina in Minsk.

On October 31st, 1959, a young man strolled into the American Embassy in Moscow. In front of an embassy officer, the man proclaimed that not only was he defecting to the Soviet Union—America’s sworn enemy at the time—but, furthermore, he was going to furnish the Russians with the secret knowledge he had acquired through his stint in the US Marine Corp. He threw down his American passport on the officer’s table, renounced his citizenship, and stormed out. The passport’s name read, “Lee Harvey Oswald.”

Oswald in target practice

Three years earlier Oswald had enlisted in the Marine Corp in order to both follow in his brother’s footsteps, whom he looked up to greatly, and to escape the clutches of a controlling and mentally-unstable mother.

Once in the Corps, Oswald nurtured a curiosity-turned-obsession of Marxism, which earned him the nickname “Oswaldavich” from his fellow Marines. He was trained first as a sniper, registering himself at marksman-level on the shooting range, and then as a radar operator.

Because Oswald’s job as radar operator was at a top-secret CIA airbase in Atsugi, Japan, some of his knowledge included highly-classified information on the technical aspects of the CIA’s ultra-secret U2 spy plane, which at the time made regular high-altitude surveillance flights over the Soviet Union.

Oswald, in his job capacity, would have known the U2’s maximum flying altitude, its range, its airspeed, and its radio codes—in other words, everything that the Soviets would need to know in order to shoot one down. Six months after Oswald walked into the American embassy and threatened to tell the Russians all he knew, the Soviets would accomplish exactly that when they downed a U2 piloted by American Francis Gary Powers.

CIA spymaster, James Jesus Angelton

The CIA’s counterintelligence department, run by a spooky and legendary figure named James Jesus Angleton (portrayed by Matt Damon in the 2006 film, The Good Shepherd), quietly opened up what is known within the Agency as a “201 file” on Oswald. A 201 file is basically a dossier on someone the CIA views as a potential security threat or person of intelligence interest. As writer John Newman—who was himself a career intelligence analyst—discovered in his research, the CIA’s counterintelligence division began tracking Oswald’s whereabouts and generally showing a keen interest in the ex-Marine.

The FBI also learned about his threats in the American embassy to disclose secrets to the Russians. They issued a “Flash” on Oswald, which effectively put Oswald on a national security index, or watch list, that was relayed to all FBI field offices. A “Wanted Notice Card” was sent throughout the Bureau, notifying all offices to forward any information they may come upon regarding Oswald to Division 5, the Bureau’s espionage section.

Over the next two years, as Oswald lived and worked in the city of Minsk, Russia, the American embassy in Moscow, the CIA, and FBI kept regular tabs on him. Eventually, Oswald grew disenchanted with life under Soviet communism, and wanted to return to the United States with his new Russian wife, Marina. Despite having committed treason—by both defecting and threatening to provide classified information to America’s sworn enemy—the State Department loaned the Oswalds the money to return. They left for the United States in June of 1962.

Home Sweet Home

Oswald and his new Russian wife, Marina about to embark on their journey back to the United State from Russia.

The CIA has always maintained that they did not debrief Oswald upon his return from Russia. However, in 1994, PBS’s award-winning investigative journalism program, Frontline, interviewed a retired CIA officer named Donald Deneselya who clearly remembered reading an agency debriefing transcript of an ex-Marine who defected to the Soviet Union. “I received across my desk a debriefing report,” stated Deneselya. “It was a debriefing of a Marine re-defector. He was returning with his family from the Soviet Union and was back in the United States. The report was approximately four to five pages in length. It gave a lot of details about the organization of the Minsk radio plant. It was signed off by a CIA officer by the name of Anderson.”

The Minsk radio factory is where ex-Marine Oswald worked during his time in Russia.

Frontline was able to corroborate Deneselya’s story from two different sources. The first source was a memorandum in Oswald’s declassified CIA file at the National Archives in Washington D.C. Frontline investigators saw that the memorandum contained handwritten notes in the margin that read, “Andy Anderson 00 on Oswald.” The symbol “00” turned out to be the CIA’s internal code for their Domestic Contacts Division. So, as Deneselya claimed, a CIA officer by the name of “Anderson,” apparently of the Domestic Contacts Division, had handled Oswald’s files. It is also important to note that the Domestic Contacts Division would have been the department at CIA to debrief a person like Oswald upon his return from the Soviet Union.

Frontline also interviewed the former Deputy Chief of Domestic Contacts for the CIA. He confirmed Deneselya’s story that Oswald had been debriefed by the agency upon his return.

While the CIA continues to deny what had already been proven, it has always been public knowledge that the FBI conducted a preliminary interview of Oswald upon his return. According to the agents who interrogated him, the recent defector was cold, uncooperative, and even belligerent. They finally let Oswald go, but they also notified other field offices to keep a watch on him.

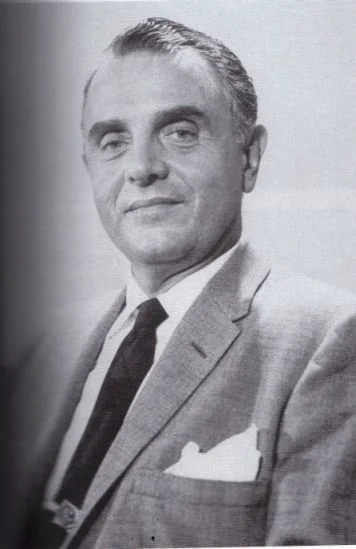

George de Mohrenschildt

The Oswalds settled in Dallas, Texas, where Lee’s brother, Robert, and his mother, Marguerite, were living. Oswald was soon befriended by an eccentric and mysterious character named George de Mohrenschildt, an oil geologist and prominent member of Dallas’ White-Russian community whose politics were vehemently anti-communist.

It was long a great mystery why a man like de Mohrenschildt would befriend a self-professed Marxist like Oswald—a mystery until it was later discovered that de Mohrenschildt’s CIA handler, J. Walton Moore, an official in the Agency’s Domestic Contacts Division (like Andy Anderson), had given the go-ahead for him to befriend Oswald. "I would never have contacted Oswald in a million years if Moore had not sanctioned it," de Mohrenschildt later told journalist Edward Jay Epstein hours before blowing his own head off with a shotgun. "Too much was at stake."

In addition to the CIA, the local FBI field office in Dallas also began surveillance on Oswald. Agent James Hosty was assigned to the case. In March of 1963, Hosty began looking into the Oswalds, being particularly interested in Oswald’s wife, Marina, because of her native-Soviet background. In June, Hosty discovered that the Oswald’s had left the Dallas area two months earlier for New Orleans. The case was turned over to the New Orleans field office.

Big Trouble in the Big Easy

Oswald handing out his "Hands Off Cuba!" leaflets on a New Orleans street corner.

While living in New Orleans, Oswald ostensibly started up a one-man chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), a pro-Cuba, communist organization, based in New York City, that advocated a normalization of relations between the United States and Castro’s Cuba. Oswald quickly began printing and handing out FPCC leaflets on the city’s streets.

Oswald soon became employed at the Reily Coffee Company, whose owner, William B. Reily, was a major backer of anti-communist organizations like the Information Council of the Americas (INCA) and the Crusade to Free Cuba Committee. Interestingly, the company’s offices were also situated in the heart of the city’s intelligence district. Just down the street were the field offices of the FBI, CIA, the Secret Service, Naval Intelligence, and a building that would become the subject of much speculation and controversy over the years.

One of Oswald's leaflets which has the address "544 Camp St" stamped on it. The address pointed to the Newman Building, an epicenter of anti-Castro, anti-communist militancy in New Orleans.

Some of Oswald’s “Hands Off Cuba!” leaflets had the address of 544 Camp Street stamped on them. That was the address of the Newman Building. The building is significant because it housed the offices of some of the most militant anti-communist and anti-Castro groups that were operating in New Orleans at the time. For instance, the anti-Castro group, the Cuban Revolutionary Council, once had offices there. The building also housed the offices of Guy Banister Associates, a private detective firm with very close links to the CIA, violent Cuban-exile paramilitary groups, and New Orleans’ feared Mafia godfather, Carlos Marcello.

Guy Banister, who headed the firm, was an ex-FBI agent, private investigator for Marcello, and a rabid segregationist, anti-communist, and anti-Kennedy extremist who employed informants throughout New Orleans to report on the activities of local communists, leftwing students, and liberal activists.

Oswald was seen at Banister’s offices on multiple occasions by a multitude of witnesses, including Delphine Roberts, Banister’s own secretary. Roberts would later tell journalist Anthony Summers, Oswald "...seemed to be on familiar terms with Banister and with [Banister's] office...As I understood it, he had the use of an office on the second floor, above the main office where we worked....Then, several times, Mr. Banister brought me upstairs, and in the office above I saw various writings stuck up on the wall pertaining to Cuba. There were various leaflets up there pertaining to Fair Play for Cuba.”

Guy Banister

It is bizarre, to say the least, that a self-professed Marxist like Oswald would be associating with an ultra-rightwing anti-communist like Banister. However, as we shall see, this followed a pattern of behavior by Oswald during his time in New Orleans in the summer of 1963.

On August 5th, Oswald walked into a store owned by anti-Castro, Cuban-exile activist Carlos Bringuier. Oswald told Bringuier that he was an ex-Marine and offered to train Bringuier’s exile compatriots in guerilla warfare tactics. Bringuier, who was the head of the New Orleans branch of the CIA-funded Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil (DRE), immediately suspected that Oswald was some sort of informant or agent who was attempting to infiltrate his group on behalf of local law enforcement or the FBI. He politely declined Oswald’s offer.

Days later, Bringuier and a few of his DRE men were informed that Oswald had been spotted passing out pro-Castro “Hands Off Cuba!” leaflets in downtown New Orleans. Enraged at Oswald’s seeming duplicity, Bringuier and his men confronted Oswald on the street, a scuffle broke out, and Oswald was arrested by the police.

Mug shot of Oswald after his arrest in New Orleans

Once in custody, Oswald asked to meet with an FBI agent. The FBI sent over Agent John Quigley, who interviewed Oswald for an hour. Quigley later testified before the Warren Commission that Oswald’s purpose for requesting the interview was to essentially justify his pro-Cuba activities and generally make “self-serving statements.” When Quigley pressed him on the details of his Fair Play for Cuba Committee activism, Oswald blatantly lied or refused to answer his questions. The Commission asked Quigley if he could produce his notes taken during his meeting with Oswald, but unfortunately for posterity Quigley destroyed his notes soon after the meeting.

Oswald was eventually bailed out of jail by Emile Bruneau, a friend of Oswald’s uncle, Charles “Dutz” Murret, who was a bookie for the Marcello crime syndicate in New Orleans.

A month after his arrest, Oswald strangely dropped out of sight. His whereabouts during September 1963, remain largely unknown, although investigations would later place him in Clinton parish during this period in the company of David Ferrie, a private investigator and pilot for Carlos Marcello, an associate of Guy Banister, and anti-communist extremist who hated both Castro and Kennedy.

At the end of the month, Oswald would resurface more than a thousand miles south, in Mexico City.

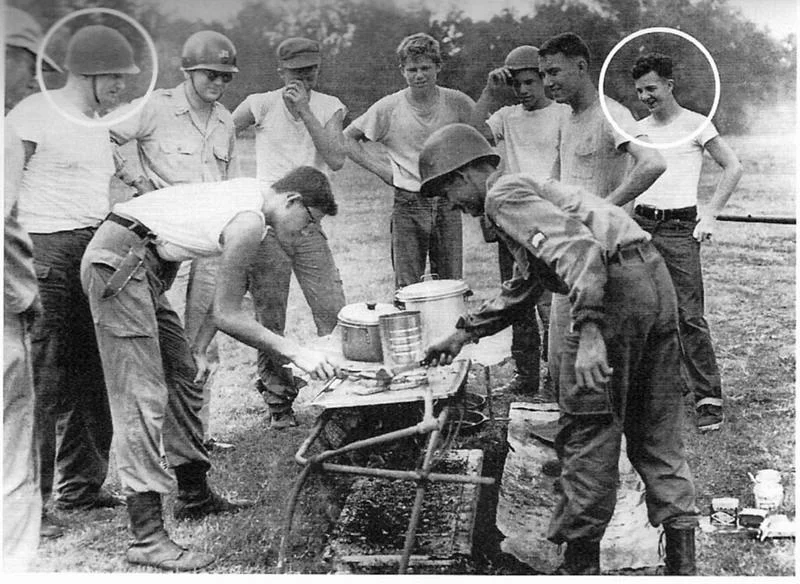

In the aftermath of the assassination, David Ferrie was fingered as a suspect by the FBI and New Orleans DA's office. Ferrie adamantly denied ever knowing Oswald, yet this photograph proves otherwise. A young Oswald stands across from Ferrie (in the army helmet) in a New Orleans Civil Air Patrol unit, circa late 50s.

Down Mexico Way

Aside from his time in New Orleans, there is no more mysterious, controversial, or potentially explosive aspect of Oswald’s saga than his trip to Mexico City. And there is no area that the CIA finds more sensitive, and is loath to discuss, than the subject of Oswald’s activities down there. In fact, the Agency has over the years gone to great lengths to hide, cover-up, and obfuscate many of the facts surrounding Oswald’s movements and associations with people in the Mexican capital. The question is why?

What has been established is that at 11:30 AM on September 27th, 1963, Oswald strolled into the Cuban consulate in the Mexican capital and applied for a transit visa to Russia by way of Havana. However, it was later discovered that this was a ruse. Oswald had no real intention of going to Russia; only to Havana.

He was told by the receptionist, a pretty young woman named Silvia Duran, that he would need to get passport photos taken. She also informed him that he would have to first get permission to reenter the Soviet Union before a transit visa through Cuba could be issued. He returned an hour later with the passport photos and then headed over to the Russian Embassy. He met briefly with the embassy’s vice council, a man named Colonel Oleg Nechiporenko, who was in fact an undercover KGB officer. He was told it would take four months for the Soviets to grant him a visa. An exasperated Oswald exploded, telling Nechiporenko, “This won’t do for me! This is not my case! For me, it’s all going to end in tragedy!” He angrily marched back to the Cuban consulate and falsely informed Duran that the Russians had granted him a visa. When Duran checked with the Russian embassy and was told otherwise, Oswald again exploded and had to be forcibly ejected from the consulate grounds.

The following day, September 28th, Oswald again visited the Russian Embassy and this time met with three embassy officials—all undercover KGB officers. In addition to Nechiporenko, Oswald also talked with Pavel Yatskov and Valery Kostikov (After JFK’s assassination, Oswald’s meeting with Kostikov would take on great significance and shake the highest echelons of the American government, for Kostikov was the KGB’s agent in charge of assassination operations in the Western Hemisphere).

During the meeting a paranoid Oswald informed his Soviet hosts that the FBI was after him and took out a gun to show how frightened he was for his personal safety. Kostikov calmly took the gun away from Oswald and emptied it of its bullets. In the end, Oswald was again rebuffed, shown the door, and given his unloaded firearm back.

As Oswald shuttled back and forth between the Cuban and Russian embassies on September 27th and 28th, the CIA was watching him closely. He came under the eye of three highly-classified surveillance programs targeting these compounds. Two of the programs, LIEMPTY and LIERODE, were operations that put both embassies under close photographic surveillance from hidden observation posts. Anyone entering or leaving the embassies would be secretly photographed. The third program, LIENVOY, was a sophisticated electronic eavesdropping operation that wiretapped the phone lines running into the embassies.

Oswald’s visits to the embassies would be picked up by all three programs.

Thus, some of the CIA’s secrecy surrounding Oswald’s trip to Mexico City could be explained by the Agency’s understandable desire to protect its sensitive surveillance programs, sources, and methods for gathering intelligence.

However, the CIA, through its close surveillance of Oswald, also picked up something that was at once baffling, disturbing, and incredibly explosive. It appears that although Oswald was indeed in Mexico City, and visited both the Cuban and Russian embassies, the CIA documented another individual, or individuals, attempting to impersonate him.

Evidence of this comes in a series of phone calls that the CIA intercepted on September 28th and October 1st. In the first call, on the 28th, a call ostensibly came to the Russian embassy from the Cuban consulate. The first speaker was someone the CIA later identified as the receptionist, Sylvia Duran. She told the Russian representative that there was an American with her who claimed to have been to the Russian embassy and wanted to talk to them. The woman then passed the phone to the American. The American insisted that they converse in Russian. They had a short conversation with the American speaking what the CIA translator later described as “terrible hardly-recognizable Russian.”

The problem is that the real Oswald was very fluent in the Russian language—so much so that Marina, Oswald’s Russian wife, thought Oswald was actually Russian when she met him four years earlier in Minsk.

The transcript of this conversation reads:

American: “I was just now at your embassy and they took my address.”

Soviet: “I know that.”

American: “I did not know it then. I went to the Cuban embassy to ask them for my address because they have it.”

Soviet: “Why don’t you come again and leave your address with us. It is not far from the Cuban embassy.”

American: “Well, I’ll be there right away.”

Another major issue is that Duran has repeatedly denied she had ever taken part in such a phone call on the 28th, for she stated that the Cuban consulate was closed to the public that day. Vice consul Nechiporenko at the Russian embassy also maintained that it would have been impossible for this call to have taken place on the 28th because the switchboard at his embassy was closed.

This begs the question: if Durran and Nechiporenko claim that they did not partake in this call on the 28th, then who made the call, which the CIA intercepted? Either Durran lied to investigators about the real Oswald not being at her consulate that day, or there was someone there who was impersonating Oswald.

The other call occurred on October 1st. At 10:30am a call came into the Russian embassy and was answered by a guard on duty. Again, the American, later identified by CIA specialists as the same voice of the call on the 28th, spoke in terrible Russian.

American: “Hello, I was at your place last Saturday and I talked to your consul. They said they’d send a telegram to Washington, and I wanted to ask you if there is anything new?”

The guard told the American to call back on another line. At 10:45 the American called again.

American: “This is Lee Oswald speaking. I was at your place last Saturday and spoke to the consul, and they said they’d send a telegram to Washington, so I wanted to find out if you have anything new. But I don’t remember the name of that consul.”

Soviet: “Kostikov. He is dark?”

American: “Yes, my name is Oswald.”

Soviet, after a pause: “They say that they haven’t received anything yet.”

American: “Have they done anything?”

Soviet: “Yes. They say that a request has been sent out but nothing has been received as yet.”

American: “And what…”

Soviet hangs up on caller.

If these calls to the Soviet Embassy were made by an Oswald imposter it suggests a few possibilities: one, that someone was attempting to impersonate Oswald to discern what exactly the Cubans, Soviets, and Oswald had discussed inside the embassies.

The other possibility, which is fraught with extraordinary consequences, is that someone or some group was impersonating Oswald at that time in order to link him, and the future assassination of Kennedy, with Valery Kostikov, the KGB’s preeminent officer in charge of assassination operations in the Western Hemisphere. This would, in effect, point to a sophisticated effort to frame the Cubans and Soviets for the murder of Kennedy—proof of a conspiracy in the assassination of the President.

Interestingly enough, after the assassination the CIA would claim it had accidentally erased the recordings of these Oswald phone intercepts, saying that it was a routine matter to erase tapes after transcription so that they could be recycled for further surveillance. As we will see, this was completely false: copies of the tapes were made, stored away, and numerous officials would admit listening to them during the investigations following Kennedy’s murder.

The CIA would also capture photos of Oswald.

The agency’s LIEMPTY and LIERODE photo surveillance operations picked up Oswald as he entered and exited both the Cuban and Russian embassies. However, these photos, like the tape recordings of the phone intercepts, have never been released. The CIA even went so far as to preposterously claim that its surveillance cameras were broken and were being repaired during the time Oswald was in Mexico City, and thus photographs of Oswald were never taken.

This is also a provable lie. Both Stanley Watson, the deputy chief of the Mexico City CIA station from 1965 to 1969, and Joseph Piccolo, a counterintelligence officer who worked at the station, told congressional investigators that they had seen these surveillance photos in the station’s Oswald file. Watson described seeing a photo that was a “three quarters from behind photo—basically an ear and back shot.” Similarly, Piccolo had seen two photos and that “these two pictures had been taken of Lee Harvey Oswald either entering or leaving the Cuban Embassy/Consulate in Mexico City. The first picture was a three-quarters full shot of Oswald exposing his left profile as [he] looked downward. The second photograph which Mr.Piccolo recollected seeing was a back of the head view of Oswald.”

Win Scott, the chief of the CIA’s Mexico City station, later admitted that photos of Oswald did indeed exist. His assistant, Ann Goodpasture, even told congressional investigators that she had duplicates of both the audiotapes and photos made, which Scott stored away in his personal safe. When Scott passed away in 1971, none other than James Jesus Angleton, the CIA’s counterintelligence czar, flew to Mexico city to personally remove boxes of Scott’s personal files as well as the contents of his safe. CIA Director Richard Helms would later tell congressional investigators, “There may have been some concern that maybe Scott had something in his safe that might affect the Agency’s work.” That “something” almost certainly included copies of the Oswald phone intercept audiotapes and surveillance photographs.

Transcripts of White House phone calls that were declassified in 1992 reveal then Vice President Lyndon Johnson and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover discussing the explosive fact that Oswald had been impersonated in Mexico City. The day after Kennedy was killed, on November 23rd, the following exchange took place when Hoover called President Johnson at the White House:

LBJ: “Have you established any more about the visit to the Soviet embassy in Mexico in September?”

Hoover: “No, that’s one angle that’s very confusing, for this reason—we have up here the tape and the photograph of the man who was at the Soviet embassy, using Oswald’s name. That picture and the tape do not correspond to this man’s voice, nor to his appearance. In other words, it appears that there is a second person who was at the Soviet embassy down there. We do have a copy of a letter which was written by Oswald to the Soviet embassy here in Washington…now if we can identify this man who was at the…Soviet embassy in Mexico City…”

A photograph, misidentified as Oswald, sent from the Mexico City CIA station to the FBI on November 22, 1963. The man in the photo is obviously not Oswald.

Earlier that same day copies of at least one Oswald phone intercept audiotape, and a photograph of a man who the CIA mistakenly identified as Oswald, were sent to the FBI field office in Dallas where agents listened to the CIA tape and viewed the photograph. Hoover’s aid, Clyde Belmont, spoke by phone to the head of their Dallas office, a man named Gordon Shanklin. Belmont later reported, “Inasmuch as the Dallas agents who listened to the tape of the conversation allegedly of Oswald from the [censored] and examined the photographs of the visitor and were of the opinion that neither the tape nor the photograph pertained to Oswald.”

In the months after the assassination when the Warren Commission was formed to investigate the murder of Kennedy, the Commission sent two of its leading investigators down to Mexico City to ascertain what Oswald had done during his stay there. The investigators, lawyers Bill Coleman and David Slawson, visited the CIA station within the confines of the American embassy. They were led to a CIA safe room in the underground bowels of the embassy. Win Scott briefed the two men on what the CIA had known about Oswald’s movements and associations during his visit in September, 1963. He showed Slawson and Coleman transcripts of Oswald’s calls to the embassies but denied they had photographed Oswald, a statement that Scott certainly knew to be a lie. As they were leaving, Scott asked the men if they wanted to hear the audiotapes—tapes that the CIA was telling everyone else did not exist. Slawson was in a hurry to leave and declined; however, Coleman listened to the tapes and later admitted to doing so.

In the final analysis, the CIA’s cover-up of Oswald’s sojourn to Mexico City can be explained by the desire to hide two very inconvenient truths: that the Agency had the President’s assassin under close surveillance in the months before Dallas, thus possibly having been in a position to have prevented the assassination. Secondly, and most damagingly, was the fact that someone or some group had impersonated Oswald in Mexico, linking the assassin of the American president with the Soviet’s premier officer in charge of assassination operations in the Western Hemisphere.

That is also most likely why the CIA disappeared its copies of the phone intercept audiotapes and photographs of Oswald: to hide the fact that they had also captured an Oswald imposter in their surveillance of the embassies, and, by extension, to hide evidence of conspiracy in the assassination of the President.

Back to Dallas

Oswald left Mexico City on October 2nd and arrived in Dallas the next day. He immediately began looking for employment.

Meanwhile, the FBI was about to make a catastrophic mistake. As noted earlier, when Oswald defected to the Soviet Union in 1959, the FBI sent out a “Flash” to its offices and placed him on a national security index or watch list. On October 9, an FBI official named Marvin Gheesling, a supervisor in the Soviet espionage section at FBI headquarters in Washington, inexplicably removed Oswald from that security index. The timing of Gheesling’s actions could not have been worse. The very next day, the FBI received information from the CIA about Oswald’s activities at the Cuban and Russian embassies in Mexico City. Had Oswald still been on the index, the explosive details surrounding his trip to Mexico could have triggered a security-alert that would have in turn alerted the Dallas FBI field office and the city’s police department that Oswald was a dangerous national security threat. That information undoubtedly would have been passed to the Secret Service before Kennedy’s trip to Texas, and they would have possibly put Oswald under intense surveillance, thus thwarting the assassination. By taking Oswald off the national security index, Gheesling had signed John F. Kennedy’s death warrant.

In one of the great tragedies of history, one week after Gheesling’s ghastly blunder, Oswald found employment at the Texas School Book Depository, a building that, from a security standpoint, overlooked precisely the most vulnerable point in Kennedy’s future motorcade route.

James Hosty, the FBI field agent who had been assigned to watch Oswald in Dallas, was made aware on October 25th of Oswald’s recent visit to Mexico City. Clearly alarmed, Hosty doubled his own efforts to tracking down the elusive Oswald who was then living under an alias at a rooming house in the Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas. He visited Oswald’s wife, Marina, twice at the residence of Ruth and Michael Paine, a couple who had recently taken Marina and her two children in.

When Marina informed her husband that she had been visited by the FBI, he was infuriated. Two weeks before Kennedy’s arrival—estimated to be either November 6,7, or 8th—Oswald walked into the Dallas FBI field office looking to confront Hosty about “harassing” his wife. Told by the receptionist that Hosty was away, Oswald left a note for him. There are differing accounts over what the note stated. The receptionist remembered it conveying some sort of threat, saying if Hosty did not leave Marina alone, he was going to blow up the FBI and Dallas Police offices. Hosty, on the other hand, remembered the note saying something more innocuous: "If you have anything you want to learn about me, come talk to me directly. If you don't cease bothering my wife, I will take appropriate action and report this to the proper authorities."

Whatever the note said, there is no way to know for certain because on Sunday, November 24th, three hours after Oswald was himself assassinated by Jack Ruby, Hosty was ordered to destroy the note by his superior, Special Agent in Charge J. Gordon Shanklin. Hosty was called into Shanklin’s office where Shanklin reached into his desk drawer and took out Oswald’s note and a memorandum Hosty had written about it. He told Hosty to get rid of it. Hosty started tearing up the note and memo. “No, get it out of here,” Shanklin said. “I don’t even want it in this office. Get rid of it.” And so Agent Hosty walked to the bathroom where he flushed Oswald’s letter and his memo down the toilet, thus destroying key evidence in the President’s assassination.

November 22, 1963

John and Jackie Kennedy riding through the streets of Dallas on November 22, 1963. He would be assassinated shortly after this photo was taken.

On November 21, the day before the Kennedys were due in Dallas, Oswald visited his estranged wife and child for the last time at the home of Ruth and Michael Paine. He tried to reconcile his marital problems with Marina, but was rebuffed.

Early the next morning Oswald retrieved his 6.5 mm caliber Mannlicher–Carcano rifle from the garage, disassembled it, and wrapped it up in the brown paper. He did not say goodbye to his sleeping wife; instead, he left his wedding ring and $170 in a cup on her dresser. He hitched a ride to his workplace, the Texas School Book Depository, with his co-worker, Wesley Frazier. While driving, Frazier glanced over and asked Oswald what was in the brown paper bag he had with him. “Curtain rods,” Oswald replied.

Meanwhile, in Fort Worth, John Fitzgerald Kennedy woke at 7:30 in the morning in a luxurious suite at the Hotel Texas. In bed next to him was his beautiful wife, Jacqueline Kennedy. The Kennedy’s had come to Texas just five days earlier in order to smooth over political feuding within their own Democratic Party between Texas Governor John Connally and the state’s Senator Ralph Yarborough. They were there also to drum up support in the deep South in anticipation of the upcoming 1964 election season, which in all likelihood was going to be a hard-fought contest, perhaps against the President’s old nemesis, Richard Milhous Nixon.

Over breakfast with Jackie and his close aid Kenny O’Donnell, Kennedy came across a curious and sizable advertisement while reading the local Dallas newspaper. Paid for by “The American Fact-Finding Committee,” and framed by a thick black border, the ad’s headline blared, “Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas…” The ad then proceeded to level numerous accusations at the President, accusing him of betraying the country to international communism. It was paid for by Nelson Hunt, the son of the state’s premier oil-baron, H.L. Hunt, and also Bum Bright, who would later go on to own the Dallas Cowboys football team. “We’re heading into nut country today,” the President told his wife and O’Donnell. They both seemed anxious, but Kennedy was fatalistic about the dangers he faced in Dallas. “But Jackie,” said Kennedy, “if somebody wants to shoot me from a window with a rifle, nobody can stop it, so why worry about it?”

Air Force One landed at 11:38 AM at Dallas’s Love Field airport. The Kennedy’s, dressed elegantly and looking every bit the movie star couple, disembarked from the plane to great fanfare from the surrounding crowd and press. They climbed into their waiting limousine. The motorcade made its way out of Love Field, heading for downtown Dallas.

As the motorcade proceeded into the canyon of the office buildings downtown, both sides of the street were lined with screaming crowds of fans and onlookers. John and Jacqueline Kennedy waved and smiled back.

Meanwhile, on the sixth floor of the School Book Depository in Dealey Plaza, an assassin was hurridly stacking boxes by an open window in order to rest his rifle on.

At 12:29 PM, Kennedy’s motorcade entered Dealey Plaza, turning from Main Street on to Houston Street. Kennedy’s limousine proceeded up Houston Street toward the Texas School Book Depository.

Right beneath the Depository, Houston Street turned sharply on to Elm Street and it was necessary for Kennedy’s limousine to slow to a crawl in order to make the sharp ninety-degree turn.

Up on the sixth floor of the Depository, an assassin steadied himself by the open window, peering down his rifle’s scope.

Over a thousand miles away, in the wealthy suburbs of McClean, Virginia, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, brother to President John F. Kennedy, was sitting by his pool at his estate, taking his regular lunch break. Robert Kennedy was unwinding from the morning’s busy meetings at the Department of Justice headquarters where he had been discussing with his team of crack prosecutors how to bring more indictments and prosecutions against leading national Mafia figures. The phone suddenly rang. It was J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI. “I have news for you,” Hoover curtly told Kennedy. “The president’s been shot.” Twenty minutes later, Hoover called again. “The President’s dead,” abruptly hanging up.

A thunderstruck Robert Kennedy immediately swung into action, dialing phone number after phone number, trying to ascertain what exactly happened in Dallas and who may have been responsible for his brother’s murder. He phoned, amongst others, the Secret Service, the CIA, associates in the Cuban exile community, and his own Justice Department‘s Mafia investigators.

Getting a ranking CIA official on the phone, Kennedy asked, his voice shaking with fury, “Did your outfit have anything to do with this horror?” Later that day CIA Director John McCone arrived at Kennedy’s estate. The two men took a walk in the backyard. Kennedy wanted to know if the CIA had assassinated his brother. Robert Kennedy later confided in a close friend, “You know, at the time I asked McCone...if they had killed my brother, and I asked him in a way that he couldn’t lie to me, and they hadn’t.”

In the hours that followed, the more Robert Kennedy learned about his brother’s killing and accused killer—Lee Harvey Oswald—a dark suspicion quickly formed in Kennedy’s mind that day, a suspicion that would haunt his thoughts until his own assassination in 1968: that top-secret covert operations, operations that he personally oversaw—involving a macabre nexus of CIA operatives, militant Cuban exiles, and elements of organized crime—had somehow boomeranged on him and his brother, resulting in the president’s assassination.

“There’s so much bitterness I thought they would get one of us,” Kennedy would say to his press secretary, Edwin Guthman, that day, “but Jack, after all he’d been through, never worried about it. I thought they would get me instead of the president.”

Jack Ruby shoots and kills Oswald as he is being transfered to the Dallas Country Jail from Dallas Police Headquarters.

The Colonel

In 1976, in the wake of the Watergate scandal, and revelations that the CIA had engaged in many illegal operations both domestically and internationally (including teaming up with the Mafia in the early 1960s in plots to assassinate Fidel Castro of Cuba) Congress launched another investigation of the Kennedy assassination. The House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was formed to review the findings of the discredited Warren Commission, review old and new evidence, conduct field-investigations, call witnesses, issue subpoenas, and even grant immunity to suspects.

One of the areas the Committee focused on was Oswald’s relationship with the intelligence community. They soon discovered that American Military Intelligence had their own files on Lee Harvey Oswald. When the Committee asked the Army to produce the files, they were informed that they had been destroyed.

However, the Army had failed to destroy the memories of those that had seen them.

On a cool fall evening in September, 2011, I met the former Lieutenant-Colonel for the last time. Since spring I had been working as a contractor for the government in Washington D.C., and it was only a short subway ride to the old man’s hospice, situated down the road, rather ironically, from Bethesda Naval Hospital, the place where JFK’s body was brought for autopsy on the chilly night of November 22, 1963.

I had interviewed the Colonel years earlier, documenting his amazing life adventures. We had kept in touch. Now, he had one last tale to tell.

The Colonel had begun his career during World War II in Military Intelligence, interrogating captured Nazi SS officers and leaders such as Herman Goering, the third most powerful figure in Hitler’s chain of command. He helped go after Odessa, the secret organization that aided Nazi war criminals fleeing the justice of Allied forces. During the Cold War he interrogated and spied on East German and Soviet agents in Berlin, helped run covert operations against Cuba, was stationed in Tehran during the days of the Shah, liaisoned with the Israeli Mossad, and generally lived the life of a real James Bond.

Years before our final meeting in Bethesda, the Colonel had sparked my curiosity when, one night over dinner, another guest asked him if he thought the Kennedy assassination could have been prevented. He looked down at his plate, his aging face briefly contorting in anguish. He said nothing.

Now, as I sat before him, conducting our final interview, I asked him the same question.

It has long been suspected by many researches, and even by the HSCA, that Oswald, while serving as a radar operator at a secret CIA airbase in Atsugi, Japan, was recruited by the agency. As the theory goes, he was given training in the Russian language, counter-interrogation techniques, and sent to Russia as part of a fake-defector program run jointly by the CIA and Naval Intelligence.

While the Colonel did not know whether Oswald was part of this program, he did confirm the existence of the program to me. He said that in those days, American intelligence was indeed infiltrating agents into the USSR disguised as defectors. It is curious to note that between 1959 and 1963 no less than 60 Americans defected to the USSR and then returned to the United States, many times with Russian wives.

The Colonel believed that Oswald was “a nut” but not a communist agent for Cuba or the Soviets. If he had any connection to an intelligence service, he said, it would been with the CIA. At the very least he was convinced the CIA debriefed Oswald upon his return from Russia (a fact already proven), and suspected that they may have kept a relationship with him. He explained that in those days, at the height of the Cold War, is was inconceivable that an American could defect, as Oswald did, and then return to the United States without being debriefed by American intelligence. This would have been all the more true since Oswald had threatened to turn over state secrets to the Russians—to commit treason.

Finally, the Colonel told me that he had seen a military counterintelligence file on Lee Harvey Oswald months before Oswald assassinated Kennedy on November 22nd, 1963. He described the file as being relatively thin. He skimmed through it and set it aside, obviously not knowing its significance at the time.

It is important to note that Oswald’s intelligence file would never have reached the Colonel’s desk in the first place if his colleagues had not deemed Oswald important enough to warrant a high-ranking officer’s attention. It shows that Oswald was of significant intelligence interest to the upper-echelons of Military Intelligence, in addition to the CIA and FBI.

There it was: American Military Intelligence, the CIA, and FBI, had all been aware of, and tracking Oswald well before Dallas.

Three weeks after our interview, he passed away.

Closing Curtains

John and Jackie Kennedy at Love Field, Dallas, November 22, 1963.

It is always difficult postulating hypotheticals when it comes to history. What if Hitler had been killed on the Western front in World War I? What if America had never dropped atomic bombs on Japan, ending World War II? What if John Kennedy had lived?

This last question still grips American society. We can see it in our culture with Hollywood blockbusters like Oliver Stone’s, JFK. We can see it with the intense press coverage that surrounded the 50th anniversary of the assassination. We can see it in contemporary literature, like Stephen King’s recent novel, 11/22/63, where the protagonist travels back through time to stop the Kennedy assassination from happening.

More than fifty years later, Kennedy’s ghost still haunts our collective consciousness.

Although it is impossible to know how the world would be different had Kennedy lived, what is certain is that had American intelligence “connected the dots” with Oswald’s movements and associations in the years and months leading up to Dallas, they probably would have intercepted Oswald before Kennedy’s trip there on November 22, 1963. Instead, our intelligence services acquiesced as Oswald defected to and returned from the Soviet Union; associated with violent rightwing anti-Castro and anti-Kennedy extremists in New Orleans; crossed into Mexico to visit enemy embassies; and walked into the Dallas FBI field office, possibly threatening violence, a mere two weeks before Kennedy’s arrival in Texas.

American intelligence knew of all these events, had Oswald under surveillance at crucial moments in the years, months, and weeks before Dallas, and yet failed to act until it was too late.

Picture taken by Marina Oswald of her husband holding the rifle he would later use to kill Kennedy.

END

Authors Note: The author recently reviewed Frontline’s program, “Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald,” on their website and noticed that vital footage had been edited out of the copy that is currently there for public viewing. The current transcript has also been edited to reflect the omission in the video.

The omission concerns an interview segment in the original, unedited video where a CIA case officer named Donald Deneselya is interviewed by Frontline. He asserts he personally saw a report of a CIA debriefing of an ex-Marine defector who worked at a radio factory in Minsk, Russia (that was Oswald's place of employment when he lived there).

For the transcript of the original, unedited video, please go here.